Living Well in All World Relations

All World Relations: the understanding that humans, creatures, plants, trees, and non-living entities, forces, and landforms are all interconnected.

The notion of all world relations is embedded in a common worlds framework and suggests

that all beings and non-living entities are entangled and dependent on one another. (BC ELF,

2019,P15)

Something about Sky:

Here are some dialogues about this topic.

Dialogue 1: William is a boy whose first language is not English but he can speak better English with his interest, such as airplane.

It was nap time after lunch, some of children didn’t sleep, so they were in the yard for free play.

William looked up into the sky: Look! Airplane!

I: Yeah! That’s an airplane. Let’s draw an airplane on the ground.

We draw something on the ground respectively.

William: That’s not airplane. That’s helicopter.

I: What is an airplane?

William: airplane has wings, like birds. It can fly.

Dialogue 2: Evelyn is a three years old girl, one day she showed me a grey rock.

Evelyn: This is moon rock, from the moon.

I: Oh, yes! It’s so special. It has holes in the surface, just like the moon surface.

Evelyn: It’s from the side of night.

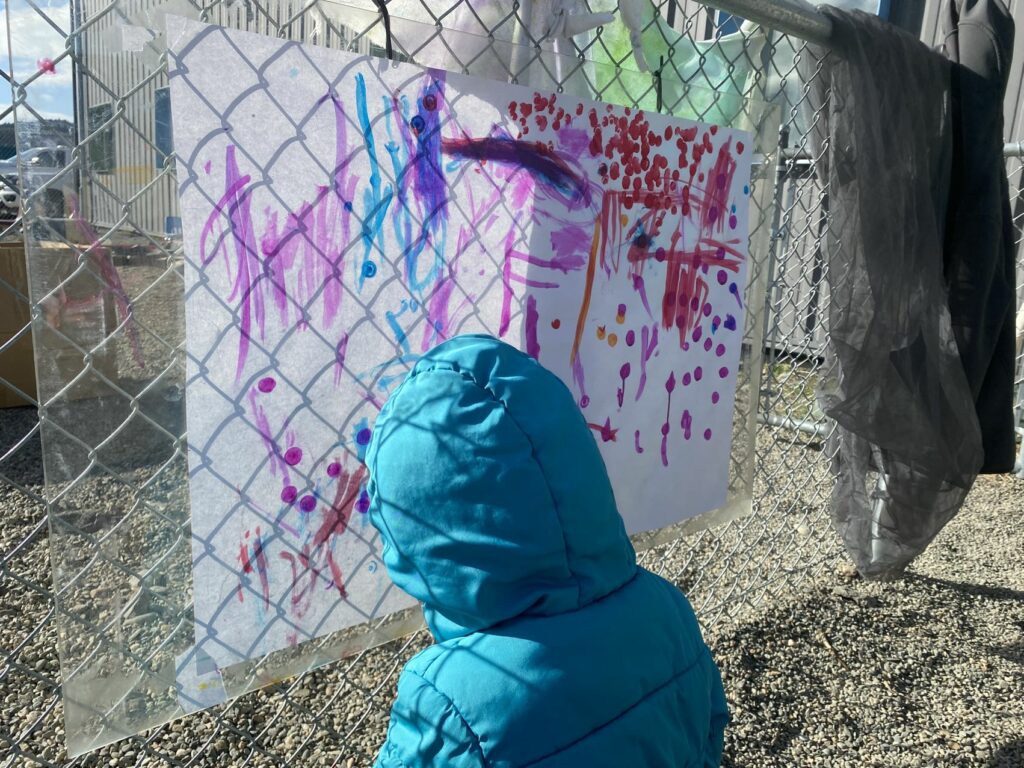

Dialogue 3: Haseli was playing paint on the white paper hung on the fence wall.

I: What are you painting? I see different bright colors on the paper!

Hesali: I am making a galaxy.

I: Galaxy? Amazing. What are in the galaxy?

Hesalie: Stars! Colors!

Dialogue 4: Finn and Aspen are two children always play together. One day they sat in the airplane mode, and I was standing near them.

Finn: Ready! Go! Let’s go to outer space.

Aspen: Finn, can we go to Paris?

Finn paused for seconds: Let’s go to outer space first, then to Paris.

Aspen: Okay.

I: What are you riding, a jet or a helicopter?

Finn: No, airplanes cannot go to outer space.

I: Then what are you riding to outer space?

Finn: Rockets. We are taking rockets.

I: Who will you meet in the outer space?

Finn paused and didn’t answer.

I: How about aliens? Do you know aliens?

Finn: I don’t know.

Looking up at the sky is something children often do. Whenever a plane flew by, the children playing in the yard always noticed it and happily told the people around them. When they played freely and talked to each other, we could hear how they understand and imagine outer space. They talked about rockets, the moon, and galaxies. These are ideas that many people in today’s world know about.

But interestingly, the word “alien,” which is common in science fiction for adults, is still new or unfamiliar to many children. Stories for children, like fairy tales, are usually about things that happened long ago—old legends or magical adventures.In the future, will “aliens” become a common word in children’s lives?

Something about Land/Place and Creatures on them.

Here are some dialogues about this topic.

Dialogue 1: A group of children were in the dog park for outdoor exploration.

I found an ant hill where some ants were in and out there, then I introduced ants to Ella who was near me.

I: Ella, Look! Ants!

Ella: Don’t touch the ants.

I: Ok, I will not touch them. Why do not touch the ants?

Ella: When you touch an ant, he will cry!

Dialogue 2: Evelyn stretched out her hand where a little bug with wings were moving forward.

Evelyn: I have a bug friend. Oh, it tickles!

The bug was about to move into her wrist covered by her sleeve, then she giggled and shook her hand, the bug dropped into the grass. Another child Reese nearby tried to get the bug with a stick.

Evelyn: No, it’s my bug friend. You cann’t take it.

Reese: No, I will not. I want to help you to get it on the stick.

But the bug hid somewhere in the grass and disappeared from the children.

Evelyn: It’s gone! It went underground. She doesn’t want to be caught.

Evelyn: She is my bug friend. She is a girl. I Don’t want her be caught.

Dialogue 3: Ava who just turned three years old was picking flowers in the dog park.

I: Eva, you already got some flowers. Stop picking them, leave these beautiful flowers for others to have a look.

Eve didn’t listen and continued picking up.

I: Eva. Do you know where are we now? We are in the dog park. If you picked up all the flowers, dogs may fell upset, no flowers left for them to have a look.

Eve: No. Dogs don’t like flowers.

Then Eva snipped all the flowers near her and then tore them apart. She looked happy to do this exploration about picking and taking apart.

Do we have to stop children from picking wildflowers, even though it makes them happy, just because we feel in our hearts that it’s better to leave the flowers growing in the ground? How can we find a balance between these two ideas? How can we talk with children about this in a better way?

Something about Peer Interactions – Inclusion

Dialogue 1: Aspen and Finn were making cakes in the sand box, while Jenny and Ella were playing there too.

Finn /Aspen: This is the cake for you.

I: Thank you. The cake looks really nice.

Jenny and Ella looked at us interestingly.

I: Can we invite Jenny and Ella have some?

Aspen: No!

I: Why?

Aspen: They don’t play with me.

I: Why you say that?

Aspen: I’ve asked them to play with me, and they always said no.

The Spontaneous Event – The Big Show

One day, I saw Reese and Aspen singing together. It felt like a stage performance—their singing, expressions, and movements were all so lively and in sync. I was drawn to it and couldn’t help recording a short video of them. I showed it to them, and then they suddenly had an idea: “Let’s make a show!”

They walked up to the wooden platform and said to the children around, “We’re going to do a show! Who wants to join?” Right away, a few children came over, including Jenny and Ella who were nearby.

The children brought some chairs and placed them in front of the platform to make an audience area. Reese and Aspen stayed on the platform, acting as both performers and hosts. The interesting part was—they invited every child in the audience to come up and perform. They followed the order of the seats, one by one.

First up was Jason. He said, “I’m a duck!” Then he jumped up and down on the stage, quacking loudly. His “quack quack” sounds were so loud that they almost covered up the girls’ singing. But Reese and Aspen didn’t mind at all. They let Jason enjoy his time on stage.

However, when Jason went back to his seat and kept jumping and making noise, Aspen warned him:”No more ducks! Otherwise, you won’t be allowed in the show.”

Later it was Ella’s turn. Reese and Aspen invited her on stage in order, and they even helped dress her up and guided her to the center of the stage.

What touched me was—Aspen had once said she didn’t want to play with Ella or Jenny. But this time, she was kind and supportive, helping them have their show time devotedly.

During free play, children often naturally gravitate toward their favorite buddies. However, when their usual buddies are absent, some children will seek out new playmates; some are able to play independently and remain emotionally regulated, while others find it harder to be alone and may show signs of emotional distress.

Occasionally, though, something special happens—like this time when Reese and Aspen spontaneously organized a singing show. Their shared enthusiasm disrupted the usual patterns of free play. They stepped beyond their usual circles of friends and created an inclusive and fair space where everyone involved in the show was treated as an equal partner.

The day after the fashion show, Reese and Aspen’s excitement about music hadn’t faded. They brought over pots, pans, and spoons from the sandbox and formed an impromptu “band.” There were four girls in total—two singing and two making sound effects. I couldn’t resist recording the lively and beautiful sounds they created. Interestingly, one of the girls was from another class, and I had never seen her play with them before.

On the third day, their passion for music continued. While playing in the backyard, they organized another concert. This time, Hesalie joined them on “stage.” The three girls even gave themselves stage names: Aspen became “Pena,” Reese was “Candy Cane,” and Hesalie was “Rainbow.” When Reese and Hesalie pretended to be fans shouting “Pena! Pena!” as Aspen went on stage, some of the younger children watching got caught up in the excitement and rushed the stage, creating a moment of chaos and bringing the concert to an unexpected end.

What stood out to me was how their choice of partners during the “concert” was so different from their usual buddy choices during free play. Why is that? Was it because of the larger, shared goal? Or was it because this was a moment of performance—with an audience?